A Quick Look At IBD

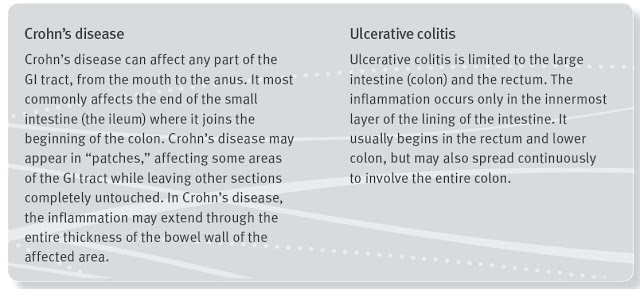

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), which includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, is a chronic, lifelong condition with serious quality of life implications. According to the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA), IBD affects as many as 1.4 million Americans, most of which are diagnosed before the age of 30. The primary characteristic of the disease is inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which manifests in symptoms that include persistent diarrhea, abdominal pain, cramping, rectal bleeding, and fatigue.

|

| Source: CCFA |

The cause of IBD is not entirely understood, but is believed to involve a number of factors including environmental influences, mucosal immune dysfunction, and genetic predisposition. Because of the variety of triggering factors, symptoms of IBD vary from person to person, and may change over time. With both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, patients go through periods of being symptom-free (remission) alternating with periods of having active disease symptoms (flare ups).

For the purpose of this article, I will focus only on ulcerative colitis (UC). For UC, the CCFA estimates patients are in remission approximately 50% of the time. Approximately 30% of UC patients will report mild disease activity during the course of a year. Another 20% will report moderate disease activity and 1-2% will report severe disease (Langholz E. et al., 1994).

The primary concerns of moderate-to-severe disease include heavy, persistent diarrhea that could lead to rectal bleeding, pain, perforated bowel, and toxic megacolon (severe inflammation that leads to rapid enlargement of the colon). After 30 years of disease, up to a third of people with UC will require surgery, which consists of removal of the colon and rectum and, in most cases, attachment of the small intestine to the anus in a procedure called an ileo pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA). Death due to UC or its complications is uncommon, as such there is really no a higher mortality rate for patients suffering from UC than the general population, except for in the most severe cases (Jess T. et al., 2007).

The Role of Eosinophils and Eotaxin-1 In IBD

Above I noted several triggering factors that lead to UC, including environmental and genetic forces. Things like smoking and diet can influence disease flare-ups, and medications such as antibiotics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may contribute to increased risk of developing IBD. However, for pharmaceutical intervention, the immune-mediated response looks to be the most viable target.

A paper by Chen et al., 2001 looked at the role of chemokines eotaxin-1, a potent and selective chemoattractant produced by epithelial and phagocytic cells, in the pathogenesis of IBD. The author found that significantly increased serum eotaxin-1 levels were observed in both patients with Crohn disease (289.4+/-591.5 pg/ml) and ulcerative colitis (207.0+/-243.4 pg/ml) when compared with healthy controls (138.0+/-107.8 pg/ml) (p<0.01). Moreover, patients with active disease showed significantly higher serum eotaxin-1 levels than patients with quiescent disease. The author concluded suggesting that this cytokine may play a role in the pathogenesis of IBD.

This work was confirmed by Mir et al., 2002 in a similar study. The author found that serum eotaxin-1 levels were significantly higher in both CD and UC patients compared to control subjects (p<0.0001), again suggesting that eotaxin-1 may be involved in the pathogenesis of IBD. Additionally, the author found that treatment with prednisone had no significant effect on disease activity.

A group of researchers out of the Division of Allergy and Immunology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine studied the levels of eotaxin-1 messenger RNA in pediatric patients with UC. The authors found that elevated levels of eotaxin-1 mRNA positively correlated with rectosigmoid eosinophil numbers, and that eosinophil-deficient mice defined an effector role for eosinophils in disease pathology and severity (Ahrens et al., 2008).

Work done by Coburn et al., 2013 showed that (A) tissue eotaxin-1 levels were significantly increased in UC patients compared to control patients, (B) the level of eotaxin-1 correlated with disease severity, and (C) the level of eotaxin-1 correlated with periods of active vs. inactive disease using the Mayo Disease Activity Index (DAI) and with eosinophil counts.

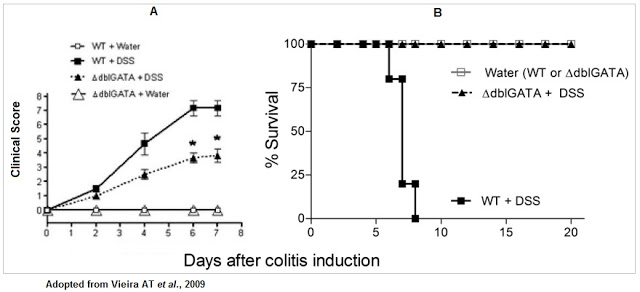

There is also overwhelming animal model data that supports the potential therapeutic target of eotaxin-1. For example, Vieira et al., 2009 showed that wild-type (WT) mice induced to symptoms similar to those seen in UC with dextran sodium sulfate had (A) higher disease activity and (B) lower overall survival than control mice or mice with genetically deleted eosinophil (delta-dblGATA).

Another study conducted by scientists at Merck Serono showed that evasin-4, a chemokine binding protein derived from tick saliva, blocks the host immuno-response, specifically eotaxin-1, by binding to CCL5 and CCL11, allowing bloodsucking parasites to feed for long periods of time without inflammation. This data supports the concept that inhibition of eotaxin-1 could prove to be a useful therapeutic target for inflammatory diseases, such as IBD (Deruaz M. et al., 2008).

Bertilimumab Blocks Eotaxin-1

Bertilimumab is a first-in-class fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody with high target affinity against eotaxin-1. The antibody binds to the aforementioned eotaxin-1 with very high affinity (~80 pM) and specificity. For example, ELISA analysis conducted using a series of human cytokines and chemokines, including the functionally related eotaxin-2 and eotaxin-3, demonstrates the high affinity and specificity of the antibody for eotaxin-1. This high degree of specificity and affinity should decrease any off-target effects or toxicities due to cross-reactivity with other antigens.

Multiple clinical and preclinical studies with bertilimumab confirm the drugs strong inhibition of eosinophil through the binding of eotaxin-1. For example, (A) bertilimumab neutralizes the ability of eotaxin-1 to cause an increase in intracellular calcium signaling, (B) neutralizes eotaxin-1 mediated CCR3-expressing cell migration, and (C) inhibits eosinophil shape change and chemotaxis in vitro (source: Immune Pharma).

Phase 2 Study Underway

Immune Pharmaceuticals (IMNP) is currently conducting a Phase 2 clinical trial of bertilimumab in patients with UC. The trial is a double-blind, placebo controlled program that will seek to randomize 42 adult patients with active moderate-to-severe UC at number of centers in Israel and Europe (NCT01671956). Eligible patients will be randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to one of two treatment groups, either bertilimumab at 10 mg/kg (30 minute IV infusion) or placebo. Importantly, key inclusion criteria include Mayo score of 6-12 (inclusive), endoscopic evidence of active mucosal disease and confirmed rectal bleeding. Patients will also have high eosinophilia, as confirmed by eotaxin-1 levels (≥ 100 pg/mg protein) from a colon biopsy.

The study will consist of three periods: a screening period of up to two weeks, a 4-week double-blind treatment period (three IV infusions at 2-week intervals), and a safety and efficacy follow-up period of approximately 9 weeks. The primary endpoint is clinical response using the UC Mayo Clinic Index two weeks after final dosing. The study indicates that clinical response will be measured as a decrease in Mayo score from baseline of at least three points and at least 30%. Secondary endpoints include mucosal injury, eotaxin-1 and eosinophil levels in the mucosa, and clinical remission. We expect results from this trial in 2016.

A Rather Large Market Opportunity

According to GlobalData, there are approximately 650,000 Americans with active UC, and another 765,000 in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK, Canada, and Japan. China and India hold another 575,000 patients. Prevalence rates are increasing by about 1% per year globally. In the U.S., there are approximately 535,000 physician office visits each year specifically for UC, with about 5-10% of these requiring hospitalization (source: CCFA). The average patient will spend over $7,500 per year in direct costs managing their disease.

While there are no medical cures for IBD, certain medications have proven to be useful in controlling disease. Generalized therapies include aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and antibiotics. Immuno-modulators that target the immune system by decreasing pro-inflammatory response, such as the tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) drugs, are also used to treat IBD. As such, some of the largest pharmaceutical companies with TNF-α inhibitors, including infliximab (Remicade®, JNJ), adalimumab (Humira®, AbbVie), certolizumab pegol (Cimzia®, UCB), and golimumab (Simponi®, JNJ), are part of the treatment paradigm. In addition to these drugs, other biologics such as natalizumab (Tysabri®, Biogen) and vedolizumab (Entyvio®, Takeda) are commonly used in severe patients as well.

J&J’s infliximab is the biologic market leader, with expected response rates of 50-55% (25-30% placebo-adjusted) based on the Phase 3 UC-I and UC-II data. Data on adalimumab and golimumab look similar, and thus affords the treating physician the opportunity to try multiple biologic therapies to find the best one suitable for the patient. While anti-TNF-α therapy has been successful for a large percentage of patients who are refractory to other conventional treatments, approximately 25-40% of patients who initially respond to anti-TNF-α therapy go on to develop severe side effects or have a loss of response to therapy over time, thus representing an opportunity for new therapeutic treatment options for these patients.

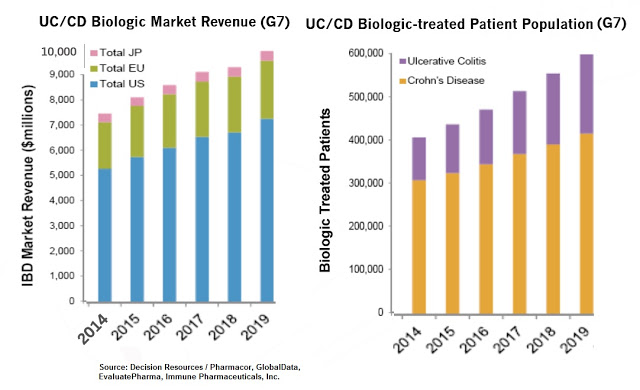

Worldwide sales of pharmaceutical products to treat IBD are expected to exceed $14 billion by 2019, with the UC market approximately 35% of that total (source: EvaluatePharma, April 2015). Biologic drugs, expensive as they are, account for $10 billion of this forecast. Crohn’s disease, the actual larger market opportunity in IBD, is certainly a viable indication for bertilimumab given the similar manifestation of the disease, and something I expect Immune Pharma to begin to discuss more in 2016 if the Phase 2 UC study is successful.

A lot of the expected growth in the IBD market will come from new treatment options, including ozanimod (Gelgene), tofacitinib (Pfizer), etrolizumab (Roche), ustekinumab (J&J), and RHB-104 (RedHill Biopharma), but UC is a complicated disease and GI physicians are actively seeking newer and more effective medications. The most practical therapeutic algorithm has been published in The Lancet by Ordas I. et al., 2013 and can been seen below.

Conclusion

The introduction of infliximab biosimilars and new treatment options such as ozanimod, tofacitinib, and ustekinumab should significantly improve patient access and treatment options for UC in the next decade. However, given the complexity of the disease and the high treatment failure rate (~50% relapse rates after one year), along with the high incidence of side-effects associated with TNF-α drugs, such as risk of serious infections and malignancies, there exists a meaningful market opportunity for additional biologic players in the current treatment algorithm. This is a $10+ billion market and over 75% of the patients on biologic drugs are not adequately being treated or have at risk for potentially dangerous side effects. Roughly 30% of UC patients and 70% of CD patients will eventually require surgery.

Immune’s bertilimumab is an interesting candidate for the treatment of IBD because of the wealth of preclinical data implicating the role of eotaxin-1 in disease pathophysiology. Additionally, the targeted approach of the current Phase 2 trial, only enrolling patients with adequate disease severity and high levels of eosinophilia confirmed by eotaxin-1 levels (≥ 100 pg/mg protein) from a colon biopsy, is supportive of a potential positive outcome for the company.