One of the most advanced clinical-stage candidates at RedHill Biopharma Ltd (RDHL) is RHB-105, a new triple combination therapy for the eradication of H. pylori infection in humans. RedHill has successfully completed a Phase 3 clinical trial with RHB-105, reporting positive results in June 2015 from the ERADICATE-Hp study. ERADICATE-Hp was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating RHB-105 as a first-line therapy for H. pylori bacterial infection. A total of 118 patients at 13 centers in the U.S. participated in the study. Subjects were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either RHB-105 or placebo for a period of 14 days, and assessed for the eradication of H. pylori infection 28 to 35 days after completion of treatment.

Top-line results from the study demonstrated RHB-105 to be 89.4% efficacy in eradicating H. pylori infection. This was highly statistically superior over the placebo and 70% benchmark use for statistical modeling (p <0.001). More importantly, following the 14 day treatment period, patients on placebo were allowed to receive a current standard of care. Follow-up analysis from this portion of ERADICATE-Hp showed these patients achieved only 63% eradication.

RedHill anticipates releasing the final Clinical Study Report in the first quarter 2016, at which time we may learn additional information with respect to RHB-105 safety/tolerability, compliance, and patient reported Severity of Dyspepsia Assessment (SODA). The next step is for management to meet with the U.S. FDA to discuss the planned second Phase 3 trial with RHB-105, which will likely include an active comparator. RHB-105 has been designated a Qualified Infectious Disease Product (QIDP) under the U.S. GAIN Act, and thus is being developed under Fast Track status. The drug will also qualify for Priority Review and a total of eight years of market exclusivity post approval. I see significant potential for RHB-105 on a U.S. and global basis. The triple combination therapy looks like it will become the new standard of care in a rapidly growing and vastly under-served market.

For the purpose of this article, I discuss the medical market perspective of H. pylori infection; the growing incidence of infection, how it relates to peptide ulcer disease (PUD) and gastric cancer, and the unmet medical need due to growing antibiotic resistance and unstandardized care.

H. Pylori – What You Need To Know

Helicobacter pylori is a Gram-negative, microaerophilic, spiral-shaped bacterium largely found in the gut (gastric species) of mammals. Like other typical Gram-negative bacteria, the outer membrane of H. pylori consists of phospholipids and lipopolysaccharide (LPS); however, the outer membrane also contains cholesterol glucosides, which are found in few other bacteria and likely contribute to the ability of the bacterium to survival in the inhospitable conditions found at the gastric mucosal surface in mammals (1).

Additionally, all known gastric Helicobacter species are urease positive and highly mobile through flagella (2). Urease is an enzyme that converts urea to ammonia, neutralizing the acidity of the stomach. This is thought to allow survival in the highly acidic gastric lumen, an area where the immune system is unable to target the pathogen. The bacterium’s flagella allow rapid movement toward the more neutral pH of the gastric mucosa lining and facilitate infection throughout the stomach. The flagella are also thought to play an important role in the export and secretion of virulence factors (3).

For the general population, the most likely mode of transmission is from person to person, by either the oral-oral route (through vomitus or possibly saliva) or perhaps the fecal-oral route. The person-to-person mode of transmission is supported by the higher incidence of infection among institutionalized children and adults, and the clustering of H. pylori infection within families. That being said, recent studies in the U.S. have also linked clinical infection with consumption of H. pylori-contaminated well water (4).

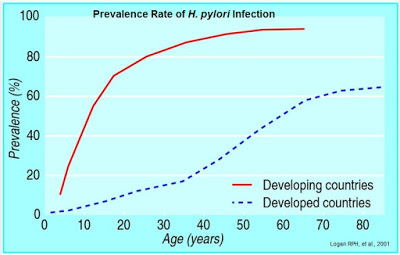

Colonization with H. pylori is not a disease in itself, but a condition that affects the relative risk of developing various clinical disorders of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In fact, H. pylori infection is rather common, with an estimated 30-40% of the U.S. population infected (5). Outside the U.S., infection rates are even higher. Literature review suggests that over 50% of the world’s population is infected with the bacterium (6). Prevalence of H. pylori is closely tied to socioeconomic conditions and more common in developing countries than in the developed world (7).

Despite being a relatively common pathogen, independent epidemiology reviews suggest that 80% to 85% of individuals infected with H. pylori are asymptomatic (8, 9). Nevertheless, both duodenal and gastric ulcer diseases are closely associated with H. pylori infection, and H. pylori is believed to be associated with the pathogenesis of infection-initiated chronic gastritis, which is characterized by enhanced expression of many inflammatory genes. The bacterium is also certainly linked to carcinogenesis and establishment of a carcinogenic environment that leads to gastric cancer (10).

An Undeniable Link To Peptic Ulcer Disease

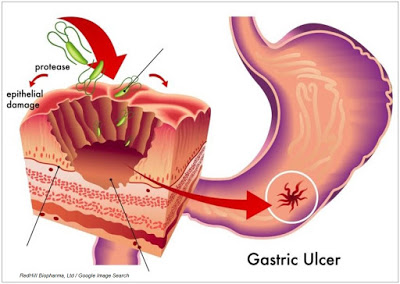

H. pylori infection is considered the key factor in the etiology of various gastrointestinal diseases, ranging from chronic active gastritis without clinical symptoms to peptic ulceration, gastric adenocarcinoma, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Work done by researchers at the University of Amsterdam shows that an individual infected with H. pylori has an estimated lifetime risk of 10-20% for the development of peptic ulcer disease, which is at least 3-4 fold higher than in non-infected subjects (11). H. pylori infection can be diagnosed in 90-100% of duodenal ulcer patients and in 60-100% of gastric ulcer patients. What is more interesting, is that after eradication of the infection, the risk of recurrence of ulcer disease is reduced to below 10% for gastric ulcer disease and to approximately 0% for duodenal ulcer disease (12).

In 2005, Barry J. Marshall and J. Robin Warren were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of “The bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease” dating back to the early 1980s. Fellow Australian gastroenterologist, Thomas Borody, the original inventor of RedHill’s RHB-105, collaborated with Marshall and Warren and is credited with developing the first FDA-approved triple therapy for H. pylori infection, called Helidac®. RHB-105 is his improved, next-generation product.

In 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified H. pylori as a Group I carcinogen. As a result of work done by Marshall & Warren, et al., it is now universally accepted that H. pylori infection causes chronic gastritis and peptic ulceration, and is the strongest risk factor for the development of gastric cancer (13).

The exact mechanism in which the bacterium is involved in the formation of peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is not fully understood, but H. pylori virulence factors such as the cytotoxin-associated gene pathogenicity island-encoded protein, CagA, and the vacuolating cytotoxin, VacA, aid in the colonization of the gastric mucosa and subsequently seem to modulate the host’s immune system. It is also understood that host genetic polymorphisms that lead to high-level pro-inflammatory cytokine release in response to infection increase the risk of cancer (14). The combination of virulence factors and pro-inflammatory cytokines proliferate epithelial cell signaling, leading to epithelial damage. Inflammation can also lead to increased acid production and duodenal and gastric ulceration, and eventual adenocarcinoma. Pathogenesis may also depend on environmental cofactors (15).

Rethinking Gastric Cancer Etiology

Gastric cancer, or cancer of the stomach, is the fifth leading cause of cancer death worldwide and fastest growing cancer in Asia (16). Gastric cancer can be divided into two main classes, gastric cardia cancer (cancer of the top inch of the stomach, where it meets the esophagus) and non-cardia gastric cancer (cancer in all other areas of the stomach). According to Globocan 2012, nearly one million individuals developed gastric cancer in 2012, representing 6.8% of all cancers worldwide. Gastric cancer is the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the world, killing nearly 725,000 individuals in 2012, representing 8.8% of all cancer deaths worldwide (17).

According to NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, an estimated 24,590 people in the U.S. were diagnosed with gastric cancer and 10,720 people died from the disease during 2015 (18). The five-year survival rate is only 29%. According to the NCI, H. pylori is the primary identified cause of non-cardia gastric cancer.

Further evidence of the link between H. pylori infection and the incidence of gastric cancer can be seen in the image below. These are two separately sourced maps combined into one figure showing the incidence of H. pylori infection around the globe (19) and the rate of gastric cancer (20). The overlap is quite telling. Areas of the world where H. pylori infection is most prevalent correlate to higher incidences of gastric cancer. As noted above, in 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified H. pylori as a Group I carcinogen.

Eradication As A Strategy

Given the now known link between H. pylori infection and clinical disorders of the upper GI tract, it is logical to pursue eradication as both a treatment option and potential prophylactic for peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer. The clinical evidence over the past decade supports this strategy. For example, a meta-analysis including 24 randomized controlled trials and randomized comparative trials including 2,102 patients with peptic ulcer disease revealed that the 12-month ulcer remission rate was 97±2% for gastric ulcer and 98±1% for duodenal ulcer in patients successfully eradicated of H. pylori infection, compared with 61±9% for gastric ulcer and 65±10% for duodenal ulcer in those with persistent infection (21).

H. pylori eradication strategy as a prophylactic for gastric cancer is still an emerging strategy, but early clinical work looks encouraging. For example, in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial conducted in China followed 435 H. pylori infected patients for 5 years after a course of anti-H. pylori therapy or placebo. The authors concluded that H. pylori eradication was protective against progression of premalignant gastric lesions (22). Another study recruited 1,630 asymptomatic H. pylori infected subjects in a high-risk region of China, and randomly allocated them to eradication therapy or placebo, after which they were followed for 7.5 years. The authors found that a subgroup of H. pylori carriers without precancerous lesions at index endoscopy had significantly lower incidence of gastric cancer following eradication therapy than in those receiving placebo (p= 0.02) (23). These independent studies, among others, supports the hypothesis that eradication of H. pylori can markedly lower the risk of developing gastric and duodenal ulcer recurrence, as well as reduce the risk of gastric cancer and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (24).

In 2014, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a division of the World Health Organization (WHO), published a report titled, “Helicobacter pylori Eradication as a Strategy for Preventing Gastric Cancer.” The 190-page IARC report concludes:

Randomized clinical trials have found that H. pylori treatment is effective in preventing gastric cancer, and models indicate that H. pylori screening and treatment strategies would be cost-effective. However, uncertainties remain about the generalizability of results and about the cost–effectiveness and possible adverse consequences of programmes applied in community settings. The Working Group therefore recommends that countries explore the possibility of introducing population-based H. pylori screening and treatment programmes, but cautions that decisions as to whether and how to implement H. pylori testing and treatment must hinge on local considerations of disease burden, other health priorities, and cost–effectiveness analyses. Moreover, these programmes should be implemented in conjunction with a scientifically valid assessment of programme processes, feasibility, effectiveness, and possible adverse consequences.

Test-and-Treat: A Proactive Approach To Combating PUD and Gastric Cancer

Given the general conclusion in peer-review and by organizations such as the IARC and NCI that eradication of H. pylori as a strategy to reduce the risk of PUD and gastric cancer seems logical, researchers have begun to look at the proactive approach of implementing “test-and-treat” procedures for patients with dyspepsia and H. pylori infection.

Dyspepsia, generally defined as “persistent or recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen” is quite common. Prevalence rates in the U.S. are approximately 25-30%, with about half associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (25). Patients with dyspepsia often take OTC medications before seeking prescription pharmaceutical products. Consultation for dyspepsia still accounts for up to 40% of referrals among gastroenterology outpatients (26) and 5% of all primary-care visits in the U.S. (27). One study out of the U.K estimated £500 million in direct costs associated with dyspepsia relief and another £500 million in indirect costs each year (28). Similar research out of Sweden pegged the total cost at $424 million in that country (29). The U.S. health-care burden is estimated at over $1 billion in direct costs alone.

The initial approach to the diagnosis of dyspepsia has traditionally been oral endoscopy, a highly accurate approach; however, generalized use does not seem to be a realistic option due to the high cost and invasive nature of the procedure. A far less invasive and more economical option is to simply test patients with suspected dyspepsia for the presence of H. pylori and subsequently eradicate when detected (30). Independent empirical analysis supports the concept of “test-and-treat” as a cost-effective and rational approach (31). The Urea Breath Test is a simple and inexpensive diagnostic to test for the presence of H. pylori infection. A test-and-treat strategy will cure most cases of underlying peptic ulcer disease and likely prevent progression to gastric cancer.

Current Treatment Options

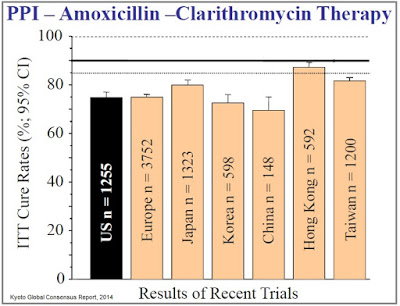

In the U.S., the recommended primary therapies for H. pylori infection include: a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), clarithromycin, and amoxicillin, or metronidazole (clarithromycin-based triple therapy) for 7-14 days or a PPI or H2RA, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline (bismuth quadruple therapy) for 10–14 days (32). When given at the recommended doses, approval studies from over a decade ago report intention-to-treat (ITT) eradication rates in the range of 80%. For example, results of the Quadrate Study (Department of Gastroenterology, Concord Hospital, University of Sydney, West, Australia) demonstrated 78% eradication for triple therapy (PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin) and 82% eradication for quadruple therapy (PPI, bismuth, tetracycline, and metronidazole) (33).

A meta-analysis conducted in 2002 comparing triple therapy (PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin or imidazole) to quadruple therapy (PPI, tetracycline, metronidazole, and a bismuth salt) found very similar results, with the quadruple therapy offering 81% eradication vs. 78% (ITT) for the triple therapy (34). Another study conducted in 2004 found a different combination of triple therapy, rabeprazole 20 mg bid., amoxicillin 1000 mg bid., and clarithromycin 500 mg bid offered 78% eradication (ITT) after 10 days (35). Large randomized trials suggest that the inclusion of amoxicillin or metronidazole yields similar results when combined with a PPI and clarithromycin (36).

A Growing Resistance

However, the trials noted above are over a decade old, and the efficacy of conventional triple therapy has decreased, with eradication rates now well below 80% (37). Areas of the world where clarithromycin resistance is high (e.g. the Middle East), eradication rates are even lower. In 2008, researchers out of the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, concluded, “The prevalence of antimicrobial drug resistance is now so high that all patients infected with H. pylori should be considered as having resistant infections” (38). The authors note that cure rates below 80% are, “No longer acceptable as empiric therapy,” and that new treatment options delivering cure rates above 90% should be the primary goal for first-line treatment.

Investigators are now establishing the bar for clinical efficacy at ~90% eradication (39), a level at which the current standard of care has failed to achieve in almost every randomized control trial (source: Kyoto Global Consensus Report, 2014).

Recall, in RedHill’s Phase 3 ERADICATE-Hp trial, a total of 118 patients at 13 clinical centers in the U.S. participated in the study. One-third of these patients randomized to placebo for the 14 day treatment period. Management at RedHill noted that the eradication rate in the placebo group after 14 days was very low, reported to be “single digits” on the conference call in June 2015. These patients were then eligible to receive “physician’s choice” standard of care, in which the most commonly used regimen was triple therapy, PPI, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin for 7-14 days. The eradication rate for this group was only 63% as reported by RedHill in September 2015. The eradication rate for the RHB-105 group was 89.4%.

RedHill’s RHB-105: A Qualified Infectious Disease Product

In November 2014, the U.S. FDA granted RHB-105 QIDP designation under the Generating Antibiotics Incentives Now Act. The GAIN Act was put into law to provide incentives for the development of new treatments for serious or life-threatening infections. These incentives includes:

1) Extending market exclusivity by an additional five years over NCE or NME status. In the case of RHB-105, RedHill will enjoy eight years of guaranteed market exclusivity for RHB-105 post-approval over the standard three for a new combination of molecular entities.

2) Fast Track designation, a provision that enables more frequent meetings and correspondence with the FDA to ensure collection of appropriate data needed to support approval. Fast Track designation also facilitates a “Rolling Review” of the application, which allows the sponsor to submit completed sections of the NDA or BLA instead of waiting until all sections are finalized.

3) Priority Review, a provision that reduces the FDA’s goal to take action on the application to six months compared to the standard ten months once all sections of the NDA or BLA have been filed.

To qualify as a QIDP, the new therapy must target a “qualifying pathogen” that shows drug or multi-drug resistance and/or pose a significant threat to public health. It is likely that the agency views RHB-105 as a QIDP because of a combination of factors, including the growing resistance of H. pylori to clarithromycin (40) and the proven causality to peptic ulcer disease and gastric cancer.

Final Thoughts

RedHill Biopharma Ltd. is a very interesting company and RHB-105 is an intriguing product. Beyond RHB-105, the company has two other Phase 3 assets in RHB-104, a fixed-dose combination antibiotic that targets mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis (MAP) as a treatment for Crohn’s disease and Bekinda®, an oral, once-daily formulation of the ondansetron for the treatment of acute gastroenteritis and irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea, along with several Phase 2 programs and a partnership with Valeant Pharma. The company exited the third quarter 2015 with $64 million in cash; and, for a company with a market capitalization of only $125 million, boasts impressive institutional ownership with names including Orbimed, Broadfin, Special Situations, Visium, Longwood, Sabby, Rosalind, and Fred Alger among its top holders.

I believe RHB-105 offers a significant commercial market opportunity for RedHill Biopharma and its commercial partner(s). Roughly 30-40% of the U.S. population is infected with H. pylori (41). Dyspepsia accounts for 5% of all primary-care office visits in the U.S. Approximately 25-30% of Americans suffer from dyspepsia (42), and 10% of the population will go on to develop gastric or duodenal ulcers (43). That equates to 22.5 million adult Americans, of which the NCI estimates roughly 1-2% will eventually develop gastric cancer. The standard of care is becoming woefully ineffective and the U.S. FDA is actively encouraging the development of new treatment options, like RHB-105.

I plan to cover the commercial market opportunity for RHB-105 in greater detail in Part-2 of my analysis of RedHill’s advanced clinical-stage candidate. Stay tuned!

Related:

Read about RedHill’s RHB-104 for the treatment of Crohn’s Disease >> HERE <<

Read about RedHill’s Bekinda for the treatment of gastroenteritis